Hello, this is Frank.

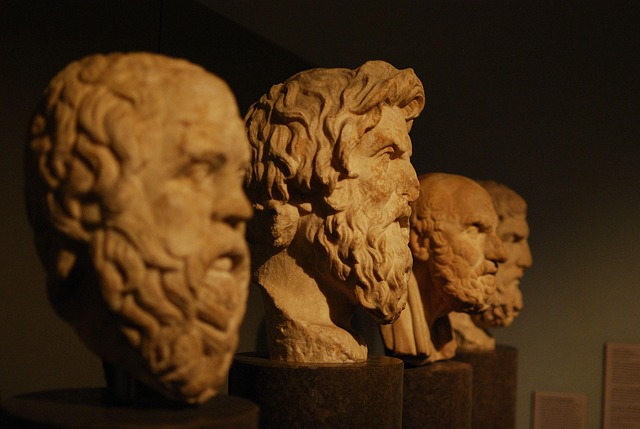

This time, we have an inquiry about <Thales of Miletus – The Father of Philosophy>.

[Question]

I can’t remember how many days ago, but after leaving a pachinko parlor, I decided to swing by the library for some free reading. A faded, light-brown philosophy book caught my eye, and when I flipped through it, I found the phrase “The principle of all things is water.” I’ve always thought the world is like a “liquid business” anyway, but does this have anything to do with the Japanese term for “mizushōbai” (the nightlife/entertainment industry)? Sorry if it’s a weird question.

– From a pachinko player living day-to-day on early-morning jackpot openings

[Answer]

Thank you for your question. Linking it to the mizushōbai is a surprisingly witty and philosophical take. Before answering, let’s first talk a bit about Thales and his famous saying, “The principle of all things is water.”

Thales (circa 624 BCE – 546 BCE) was an ancient Greek philosopher, often called “the father of Western philosophy.” Born in the port city of Miletus on the western coast of Asia Minor, he was one of the first to attempt to explain natural phenomena not through myths or legends, but through reason and observation. This shift in perspective became a cornerstone of later philosophy and science, giving Thales a unique place in the history of Western thought.

One of his most famous assertions, as you noted, was that the archē (origin or principle) of all things is water. At the time, people explained lightning, earthquakes, and seasonal changes as the whims of the gods. But Thales sought a unifying principle within nature itself, and after observation, chose water. Water can take the form of liquid, ice, or vapor; it’s essential for life; and it directly affects plants, animals, and the fertility of the land. This flexibility and universality led him to conclude, “All things arise from water, and return to water.”

Thales wasn’t just a philosopher—he was also a gifted mathematician and astronomer. One of his lasting contributions is Thales’ Theorem, which states: “Any triangle drawn with the diameter of a circle as one side will be a right triangle.” While middle school geometry students learn this today, it was revolutionary at the time. He even used it to measure the height of the pyramids by comparing their shadows to his own. The idea that massive structures could be measured using nothing more than observation and logic perfectly symbolizes the power of reasoning.

Several famous anecdotes about Thales survive. In one, he was so absorbed in observing the stars that he fell into a well, prompting a nearby farm woman to laugh, “You’re looking at the heavens but can’t see what’s right under your feet.” This became a timeless image of philosophers—eyes fixed on lofty ideals yet blind to practical matters.

But Thales was far from impractical. One year, after observing the stars, he predicted an abundant olive harvest and leased all the olive presses at low cost in advance. When harvest season came, he rented them out at high prices, making a fortune. It was his clever rebuttal to the criticism that “philosophers are poor because their work is useless”—demonstrating that he could become wealthy if he wished, but chose instead to dedicate his life to the pursuit of knowledge.

His ideas deeply influenced later thinkers. His successors in the Milesian school, such as Anaximander and Anaximenes, proposed their own archē—the “infinite” and “air,” respectively—but inherited his commitment to seeking natural explanations.

Today, we know that “all things are water” is scientifically inaccurate, but the idea remains significant. It marked humanity’s first step away from myth toward reason—a turning point in intellectual history. Thales gazed at the sky, counted numbers, listened to the flow of water, and sought universal principles. His curiosity and flexible thinking still inspire us to value intellectual exploration.

As you mentioned, in Japanese, mizushōbai refers to industries like bars, hostess clubs, and other hospitality or entertainment businesses where income depends on the customer’s goodwill—unpredictable and fluid, much like water itself. In that sense, “all things are water” could be reimagined for modern times without much of a stretch.

If Thales lived today, perhaps he’d stroll into a high-end club in Osaka’s Kitashinchi district, declaring, “For me, money is the archē! Come forth, my dear!” while charming the hostesses night after night.

By the way, Thales’ profile can be found in the reference book Philosophy So Fascinating You Can’t Sleep, which ends with a witty anecdote I couldn’t help but chuckle at.

When his mother tried to force him to marry, he said, “It’s not yet time.” Later, when pressed again, he replied, “It’s no longer time.”

I can relate. Back when I was a trading company man, my mother showed me a photo of a potential match and asked, “Will you marry?” I replied, “Not yet,” as I was busy traveling the world. Now, when friends suggest remarriage, I say, “No longer,” echoing Thales’ words.

Like water, life flows best when lived naturally—yet, like mathematics, with a touch of calculated thinking.

[Reference Book]

|

眠れないほどおもしろい哲学の本: もう一歩「前向き」に生きるヒント (王様文庫) 新品価格 |

![]() Check out my published books here.

Check out my published books here.

Thank you for reading today.

Back to Genre:>Here

Currently, I’m participating in the popular blog rankings.

Today’s ranking for [AMISTAD] is?